(click here for German version)

Hasnain Kazim (born 1974 in Oldenburg, Germany) is a journalist and author of German-Pakistani heritage. For several years he served as a correspondent for the well-known German news magazine Der Spiegel in South Asia and Turkey, where he established a reputation for his keen observations and forthright views. He now lives in Vienna and, as an author, focuses on questions of identity, language and coexistence in an increasingly diverse society. In his recent book “Deutschlandtour”, and in conversation with Bijon Chatterji, he describes racism as a genuine threat, while cautioning against the term’s inflationary use: “If everything is racism, then nothing is racism.” His appeal is for a culture of debate, for humour and for open dialogue – tools that can foster understanding and help to sustain a shared sense of “we” in Germany.

Mr Kazim, you had a career many people dream of: foreign correspondent, reporter, author at Der Spiegel, award-winning. Yet at some point you decided to leave that path. Why?

Yes, it was certainly a wonderful job. I did it for almost fifteen years: I saw much of the world, though also many terrible things. That is the nature of the profession – one reports what is newsworthy, and that is so often the unpleasant. In my region this meant terrorist attacks, extremism, authoritarian regimes, natural disasters. But I always tried, alongside that, to write about the beautiful aspects as well, because the truth is that, despite everything, the world remains, in my eyes, a beautiful place.

I greatly enjoyed being a foreign correspondent. Yet throughout those years I was also writing books – which is itself something of a dream job. Eventually I found myself in the fortunate, if difficult, position of having to choose between the two, for it became impossible to manage both: the life of a correspondent, and at the same time writing, giving readings, making public appearances. With a heavy heart I chose the path of the author. But I have not regretted that decision to this day.

Your book „Deutschlandtour: Auf der Suche nach dem, was unser Land zusammenhält – Ein politischer Reisebericht“ is a journey across Germany that ultimately poses the question: who belongs here? When you think back to your childhood in a German-Pakistani household in a rural area near Hamburg, how has your personal relationship with Germany developed or changed since then?

I grew up in a village in northern Germany – Hollern-Twielenfleth in Lower Saxony, on the outskirts of Hamburg. At least during my childhood, it was a very white environment, with hardly any newcomers. I never regarded that as a problem. My family was one of the few foreign families in the town, and at kindergarden and school I just felt part of the community.

Today I often hear people with a migration background say they never saw themselves reflected in books or films. That was never my experience. I grew up convinced that origin, skin colour and religion should not matter in how we live together. And by and large, that was how it was. But I also realised fairly early on that it was not like that everywhere. The racist attacks and acts of violence of the 1990s further politicised me as a teenager who was already deeply interested in politics.

What troubles me today is that, on the one hand, there are those who deny you your “Germanness” – speaking of “real Germans” and “passport Germans.” On the other hand, there are some who retreat into identity-driven “communities”, speaking of „Allys„, dividing themselves by skin colour and origin, accusing others of “cultural appropriation” because of the music they play, the clothes they wear, or the hairstyle they choose – even declaring it “problematic” when an old white man translates the poem of a young black woman. I find that grotesque. I cannot make anything of it, and I will not take part in it.

If someone were to confront me on those terms, I would simply put on my kimono, crown it with a sombrero, dance Kathak and eat Kohl und Pinkel.

Wonderful transition, thank you. Because already in Grünkohl und Curry you tell the story of your immigrant family. In Deutschlandtour you once again encounter people who, as you said, deny you a sense of belonging: these are quite the simple questions – “Where are you from? Will you ever go back to your homeland? You speak German very well…” How does your own migration history shape your view of the current political climate – and of concepts such as homeland or integration?

In the village I grew up, in the schools I attended, and later during my military service (Bundeswehr), where I began an officer’s career in the navy, I generally always felt that I was part of it. Of course, there were moments when I was reminded that I had a different skin colour and a name that sounded foreign, but those instances were relatively rare. The real rejection my family and I experienced came from the authorities, from German bureaucracy. Naturalisation took us sixteen years; my parents fought for years for us to become recognised as German citizens. Although I was born and raised in Germany, I only became German at the age of sixteen. We often faced the threat of deportation, living for years as “tolerated foreigners.” At one point my father even had his work permit arbitrarily withdrawn. The immigration policy of the 1980s was, to put it mildly, dreadful.

And today?

It is not entirely good, wise or in Germany’s best interests today either – but there is a genuine attempt to do better at least. Personally, I am not troubled by the question ‘Where are you from?’ On the contrary, in most cases it signals interest. The unspoken thought behind it is often: ‘You have darker skin, that is not yet so common here, so you must have roots elsewhere – may I ask where? I am curious about your life story.’ That question often leads to interesting conversations. Quite often I ask, and then I learn of ancestors from East Prussia, Bohemia or Silesia, I hear stories of flight and of new beginnings. Of course, at times the question also carries another undertone: ‘When are you going back?’ or ‘Do not imagine you belong here!’ In those moments I can find the right words. And when someone compliments me on my German, I respond in kind – lavishly, and with the subjunctive and intricate sentence structures – praising their German as excellent too. There usually follows an awkward silence, and people grasp the point: you do not need to be blond, blue-eyed Adolf to speak German well.

I must admit, I am being a little mischievous here. The compliment generally comes from the experience that not many people perceived as ‘foreign’ speak German without an accent. Just as one might be momentarily surprised if a black person spoke in broad Bavarian, or if someone you would visually place in China conversed fluently in Low German. For my part, I call the German language my home, and I am a firm supporter of the concept of integration: first and foremost, language. I advise everyone who wishes to live here permanently to learn it. But of course our shared values and social norms matter as well.

With „Post von Karlheinz“ and „Auf sie mit Gebrüll“ you have demonstrated how to meet hate with stance… and with irony. But on your bicycle trip you did not seek confrontation, rather conversation – what insights did you draw from that?

Ah, I never set out solely to provoke confrontation, nor solely to pursue understanding. Living well together requires a balance of both. Humour enables one to endure a great deal. As Ringelnatz observed, ‘Humour is the button you press to stop your collar from bursting’. A genuine insight.

Indeed…

…but if you also take the time to listen, to take people seriously, to ask follow-up questions and not fly into a rage the moment they say something you find objectionable, but instead try to understand what they actually mean, you gain a great deal of insight into the state of mind of our society. And even if it may sound like a rather simple observation, it is an important one: these are human beings, and their worries and troubles – however trivial they may appear from the outside – are real and deeply consequential for them. One has to acknowledge that and make an effort to discuss it sensibly. It does not always succeed, but often it does. And one further lesson I drew from my cycling journey: it is invariably better to speak with people directly, face to face, than to communicate online.

Many young people with a migration background face a growing shift to the right nowadays with everyday racism, and media debates about ‘remigration’. As a young person, you may already have encountered this, or experienced it in different ways. I am interested in how you navigated these challenges in the past, and what lessons you might pass on to the next generation.

In the 1990s, I experienced this in a profound and unsettling way. Houses were set alight, people were murdered. All the right-wing extremist crimes – Solingen, Hoyerswerda, Hünxe, Mölln, Rostock-Lichtenhagen, Eberswalde, and so forth – are indelibly imprinted on my memory. Witnessing this as a teenager, I felt for the first time that I might no longer be safe in my own country, and that solely because of the colour of my skin. This profoundly politicised me. At that time, I resolved to stand against it. That is also the advice I would offer to young people today: engage, speak up, and participate fully in society. But it also entails embracing your place within that society. Do not retreat into groups that segregate by skin colour, origin, religion, gender, or sexual orientation. Instead, let us understand ourselves as part of a shared ‘we’. Equally important, do not treat every question of ‘Where are you from?’ as an insult. Be measured in your accusations of racism – reserve the term for situations where it is genuinely warranted, for if it is applied indiscriminately, it quickly loses force. The question ‘Where are you from?’ can at times be slightly insensitive, particularly when, after responding ‘From Hollern-Twielenfleth!’, one is pressed further with: ‘Yes, but where are you really from?’ Yet I would not classify that as racism.

You have often described your role as a „migrant“ in Germany with a sense of humour and at times with a touch of sarcasm, as in the “Kalifat-Tagebuch” or the “Kalifatskochbuch”. In “Deutschlandtour”, however, your tone is more subdued, at moments even bordering on the melancholic. Has your perception of Germany shifted, or rather your expectation of being listened to?

I hear that quite often. People sometimes even suggest that my political outlook has changed. I have reflected on this thoroughly and my conclusion is clear: no, in essence my position has not changed. Politically I have always placed myself in the centre – leaning to the left on some questions, to the right on others. Before embarking on my journalistic career, I joined the FDP because I wanted to understand politics from within, and I regard liberalism as something valuable. My politics teacher had advised me that if I truly wished to learn, I should join a smaller party, as that would allow me to engage directly and take on responsibility. At the time, I also considered the Green Party (Die Grünen) and attended some of their events.

But I grew up in the district of Stade with a quite prominent nuclear power plant. Back then the Greens were essentially a single-issue party: everything revolved around anti-nuclear policy. I had nothing against that position, but it was not a subject that gripped me personally. Hence, I chose the FDP, which at the time was still a genuinely liberal party, alive with spirited debates on civil rights and liberties. I left the party before beginning my journalistic career.

I also served for six years in the Bundeswehr, a rather conservative environment, in which I nonetheless felt at ease. My political stance has always been, and remains, quite straightforward: to oppose extremism and ideology, to listen to every argument, to seek compromise, to defend the widest possible freedom for the individual – while recognising that limits must be drawn when one person’s freedom infringes upon another’s. And one more thing: never give stupidity a stage. That, I fear, has become one of the great afflictions of our age. Across the spectrum, stupidity has grown proud, striding noisily into public life. And because of a misguided notion of inclusion, far too few people are prepared to contradict it. That is why today, more than ever, some of the most foolish voices are able to seize political power.

You write about ruptures, about nuances, about a society that at times seems almost alien to itself. What, in your view, defines a healthy culture of argument today – and how can it succeed without people with a migration background constantly having to justify their very existence?

The philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer once said: “A conversation presupposes that the other could be right”. That, I think, captures the essence of a sound culture of dispute: allowing for the possibility that the other may be right and that you yourself may not be. Being right is not a matter of who shouts the loudest. Nor is the majority invariably right – a point often misunderstood when people speak of democracy. For, as Tocqueville warned, there can indeed be a “tyranny of the majority”; minority rights must always be safeguarded.

At its core, a good culture of argument is rooted in principles that have held true for millennia: the exchange of argument and counterargument, the sharing of ideas, a contest of the best reasoning – and ultimately, in the best case, a compromise with which all sides can live. I sometimes hear claims that this no longer exists today. But who says so? Am I not myself part of shaping that culture? I say: yes, it still exists.

What many have forgotten, however, is what freedom of expression truly means. Too often it is confused with a supposed freedom from contradiction. Yet no one is entitled to that. If someone writes or speaks nonsense, they must expect to be told as much.

As for people with a migration background: I believe this will change with time, as it becomes ever more natural that people like us are simply part of this society. Much has already shifted in recent years. But there will always be developments that generate tension, moments when people like us are put under pressure to define our position. East Germans, for instance, are often assumed to vote uniformly for the far right. Or people of Turkish origin are thought to support, unquestioningly, a perpetually aggrieved autocrat. Such stereotypes are exhausting, yes. And yet the only remedy is, and remains: to talk.

Was there a symbolic moment on your tour through Germany – something that encapsulates what holds this country together, or perhaps what it is in danger of losing?

I had so many encounters that it is difficult to single out just one. My overall impression is this: we complain too much, we look at everything through a pessimistic lens, we fear change – the prevailing mood is worse than the reality. In truth, most of us are doing rather well. What we lack is a sense of lightness, of confidence, of hope. Of course, if you are constantly told: “We will never be as well off as our parents!” then gloom inevitably creeps in. But if that simply means not having two cars parked in front of the house, perhaps sharing one with the neighbours, and reducing two long-haul holidays each year to perhaps a single trip – say, a seaside week in Cuxhaven … oh my dear!

What also struck me was how many generous, remarkable people there are who commit themselves to helping others. That is truly uplifting. And those examples are not hard to find – we often simply fail to notice them, or have forgotten how to appreciate them. Perhaps I see this more clearly because I have spent many years living in countries where a great many people really do struggle just to survive.

You lived in Pakistan, you know how people there think. How is the conflict with India perceived locally, and how distorted is the picture that reaches us through Western media?

Do we even hear much of it through Western media? It tends to be reported only when the two countries are once again thought to be on the brink of nuclear confrontation. Otherwise, we indulge in our own navel-gazing. But the situation is no different in Pakistan or India. Look at the local media there: how much do people actually learn about events beyond their own region? Almost nothing.

Most ordinary people in Pakistan – those earning a modest living, struggling to pay for their children’s schooling, rarely able to travel – have a deeply distorted image of India. For them, India is the great, unknown, menacing enemy. When I tell people that I used to travel frequently to India, they react with a mix of dread and curiosity: “What is it like there?” And when I respond: “In terms of the cityscapes, the sounds, the smells, how people live and look – it is scarcely different from Pakistan”, they are often incredulous. Strange, is it not?

… absolutely.

… because, after all, it was once one country, before the partition of the subcontinent in 1947. Many families – mine included – are partition families, with roots in both India and Pakistan. And yet, for many Pakistani, India remains the faceless, hostile enemy. That perception is, of course, carefully cultivated by the Pakistani military. For them, the spectre of India is essential: it legitimises their power, their dominance, and their vast claim on the state budget.

Thank you for taking the time to speak with us, and for giving us so much to reflect upon with your answers.

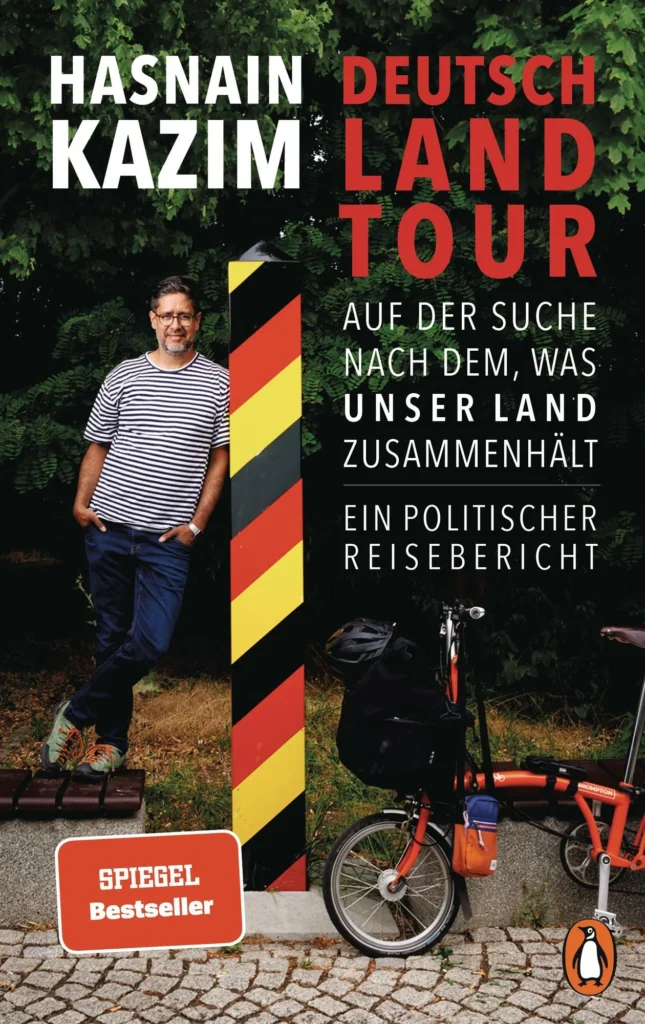

Book recommendation: „Deutschlandtour – Auf der Suche nach dem, was unser Land zusammenhält. Ein politischer Reisebericht“ by Hasnain Kazim, Penguin Verlag (2024), 352 pages, ISBN 978-3-328-60177-7

Content: One man, one country, one bicycle – Hasnain Kazim on the road in search of the German soul. Hasnain Kazim sets out to explore his country. Using his favorite means of transport, the bicycle, he embarks on a journey to create a contemporary portrait of Germany. What unites people, and what divides them? Kazim cycles along the Elbe, Ruhr, Rhine, Oder/Neisse, Neckar, and Danube rivers, leaving room for chance encounters. He meets all kinds of people and talks with them about their lives in this country: What are we still allowed to laugh about? What is “home”? The book is also a personal exploration: Some people regularly question Hasnain Kazim’s belonging to Germany. So when and how do people truly belong here? What is diversity? Can goodwill and empathy make it possible to talk with everyone – perhaps even reconcile them and bridge divides? A bicycle journey that seeks to connect through the power of words – and to explore the German soul.