(hier klicken für deutsche Version)

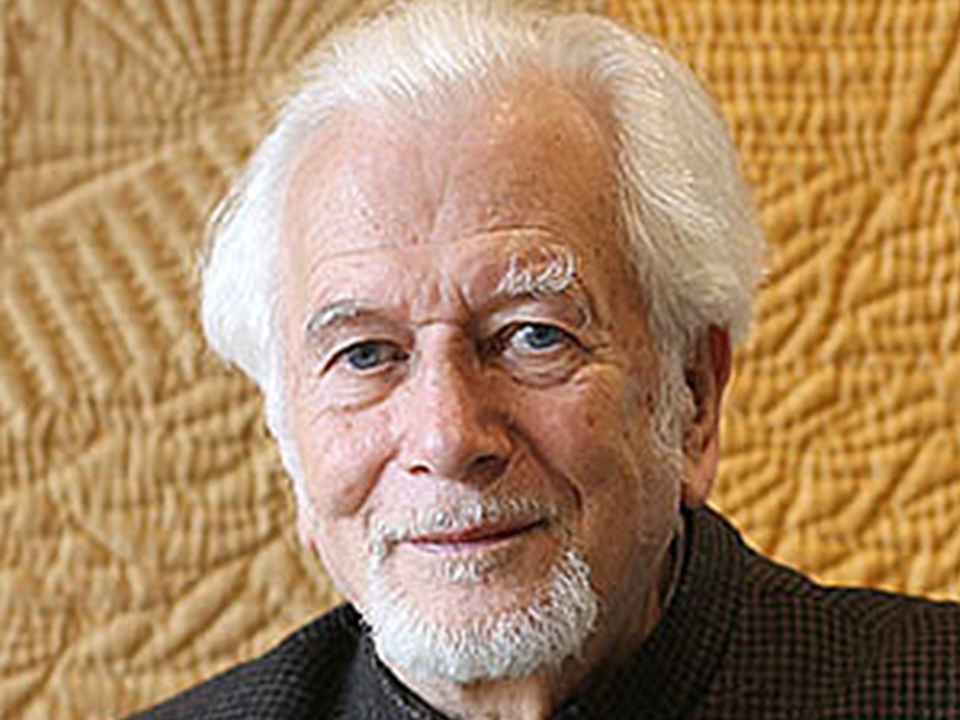

Martin Kämpchen (*1948) is one of the most important mediators between India and Germany. As a literary scholar, author, and translator, he has set standards above all through his translations of Rabindranath Tagore’s poetry into German. For his long-standing commitment to intercultural dialogue, he has been awarded, among others, the Tagore Prize of the German-Indian Society, the Federal Cross of Merit, as well as an honorary doctorate. Kämpchen lived and researched for five decades in Santiniketan, the stronghold of Tagore. In doing so, he not only rendered great services to cultural exchange but also developed a deep understanding of India’s spiritual, literary, and social diversity. In the following conversation, initially a little in Bengali and then eventually in German, he spoke with me about why Tagore is relevant today, the challenges of translation, intercultural bridge-building, and personal life decisions – an intellectual as well as deeply personal testimony of a life between two worlds.

Indian Literature & Translation

Dr Kämpchen, Rabindranath Tagore shaped the intellectual foundation of modern India: as poet, philosopher, educator, and universal scholar. In my parents‘ home „Gitanjali“ and „Shyama“ were indeed present, and yet Tagore’s literary voice in the West today seems almost silenced. It is voices like yours that keep his depth and relevance alive. But why, do you think, is that so?

In the 1920s, Rabindranath Tagore was a celebrity in Europe and particularly in Germany. He was able to console the German people over the loss of the First World War by praising Germany as a great cultural nation that would be able to rise again with the help of its cultural values. After the Second World War, Tagore was no longer read. Hermann Hesse remarked that he was being punished for his excessive popularity. The impulse to embrace him as in the 1920s was missing. Emotional, often quite pathos-laden poetry was characteristic of Tagore. But precisely emotion and pathos were frowned upon in Germany after the Second World War, because the “blood-and-soil” literature of the Third Reich had displayed too much of it. Added to this is, as you say, the matter of translation. Until then, Tagore had become known in Germany only through his own English versions of poems, not through translations from the original. Tagore’s own English versions are, compared with the Bengali originals, weak, bloodless, powerless – without metre and verse and rhyme. This shortcoming was then, after a distance of half a century, recognized.

You are considered one of the most important translators of Tagore into German. The Indian languages – above all Bengali – are rich in ambiguities, nuances, poetic imagery…

I consider Rabindranath’s poetry and his songs to be his most important creations. They are what made him a writer of world literature. That is why I concentrated as a translator on his poems and songs. Quite right, they are the most difficult to transfer into another language, especially when it is a language like German, which is culturally so far removed from Bengali. So I did not only translate from one language into my own, but also from one culture, a religion or spirituality, and an emotional cosmos.

Experts say that a word-for-word translation of Tagore is hardly possible.

They are right, translating Rabindranath’s poetry is infinitely difficult. I learned Bengali in Santiniketan, lived for decades among Bengalis, lived for decades with Tagore’s heritage and in his atmosphere in Santiniketan. Immersion in Tagore’s world was almost total. That made it possible for me to translate him – alongside a large portion of boldness, perhaps recklessness. My translations are my own, but I discussed each poem several times with various people in Santiniketan – in Bengali – and above all had each poem recited to me again and again. My claim was to translate philologically precisely and literarily appropriately. My first collection of fifty poem translations cost me four years of preparation, no less. But I will tell you something: I often despaired of Tagore’s works and abandoned quite a few translations. Ten years ago, I stopped altogether, I wanted to write my own books.

But perhaps it is also the special feature that every translation of Tagore is individual. What, for you, makes a “good” translation – is it more about linguistic closeness or about atmospheric fidelity?

A good poem is a “total work of art” of linguistic expression, linguistic melody, rhythm, rhyme, and emotionality. These levels must be precisely attuned to one another and fit together in an intuitive way. Only then is the translation perfect, if it also represents such a total work of art.

You said you wanted to write your own books. You have also written three children’s books in English?

That is true. One book appeared in German under the title Together We Are Strong. I have given readings before children, among others in Mumbai and Kolkata; the young people were enthusiastic, which made me very happy.

Spirituality & Society

Your approach to India is shaped not least by the spiritual dimension. How did you personally find your way to spirituality?

I grew up in a Catholic family and to this day I am a practicing Catholic. Becoming an adult means reconsidering and redefining one’s relationship to religion. I discovered in myself a tendency toward mysticism and inwardness and a relativization of Catholic ritualism. My search led me to a spirituality in which “faith” and ritual were not so important, but rather the search for religious “experience.” That brought me to Swami Vivekananda and Sri Ramakrishna. Added to this was a confusion typical for seriously searching young people: How can one find one’s way within the diversity of offers of how to shape one’s life, of possibilities to know and to experience?

The search for orientation…

Yes! What to do first, what after? Meditation and the reading of mystics helped me to distinguish the important from the unimportant. I describe this development in detail in my autobiography My Life in India (Editor’s note: Patmos Verlag 2022).

Observers view with concern that in India religious authorities are increasingly allowing themselves to be politicized. Is the secular character of the Indian state in danger?

Secularity, that is: the equality of religions, is, wherever it exists or is aspired to, in danger.

Why “always”?

Because religion tends toward absolutization, toward fundamentalism, as long as it does not possess a solid rational framework. Within the European cultural sphere one would say: …as long as Enlightenment and Humanism have not relativized religion. “My God is not your God – your God is not my God” is so deeply rooted in the weaknesses of human beings – in selfishness, irrationality, lack of flexibility, and lack of creativity! People do not understand: If they distinguish between “my God” and “your God,” they cannot mean God, who can only be infinite and eternal and beyond all limitation in order to be God.

India was for a long time a model for the coexistence of different religions. Do you see this strength at risk?

It is obvious that the politicization of religious life is problematic. It polarizes instead of bringing together. In politics it is about elections and majority of votes, in religion the individual choice of a particular way of life centered around a core of faith and experience is essential. In everyday life, however, I see that people of different religious backgrounds mostly work together, precisely because they depend on each other. Religion is not decisive here, but rather the best possibility to continue one’s life appropriately. And that requires cooperation, partnership, and trust in one another.

Can parallels be drawn to social development in Germany?

In Germany, religious affiliation is no longer important in everyday life. Mostly people do not know whether their business partner, the neighbors, the regulars at the pub are Catholic or Protestant. Ethnic identity is more formative and differentiating and leads to different blockages in coexistence..

Integration & Personal Change

As you said earlier, you lived in Santiniketan for many years, with the local population, in their language and way of thinking. Do you remember your first impressions?

When I arrived in Santiniketan in 1980, the place was a large village; 45 years later it is a medium-sized town. The core, that is, the “ashram,” remains untouched, but all around much has changed. There are supermarkets, large hotels, fine restaurants – much that contradicts the ethos of Santiniketan. At that time there were only two or three cars, you could still strike up a chat in the middle of the street. Pedestrians and bicycles dominated, as well as cycle rickshaws. Today I can only cross the street at risk of life. For forty years I could easily ride my bike, two years ago I gave it up…

… how did your personal integration process unfold?

Although in 1980 I already had a PhD from the University of Vienna, I enrolled at the University of Santiniketan, Visva-Bharati, to do a second doctorate. For years I was regarded as a student and was not invited to take part in academic and cultural activities in order to contribute my experiences. I remained isolated. Only one Vice-Chancellor, Professor Sushanta Datta Gupta, integrated me into the academic community and opened up various opportunities – lectures, participation in committees. The disadvantage of integration was that my work on Tagore – namely my translations, the biography of Tagore at Rowohlt Verlag, my research on Tagore’s relations with Germany – essentially took place in German, so the academic community in Santiniketan knew little about it. This, however, also allowed me to stay away from the jealousies and petty quarrels in the place.

But integration cannot only take place at the professional level…

That is of course true, integration for me almost always happened only through friendships. It was a great honor when locals considered me a friend and made no distinction as to where I came from. In addition, a five-year visa from the Indian government is also a form of appreciation – I owe that, by the way, to the then Ambassador in Berlin, Ronen Sen, with whom I am still friends today.

How did life in India change you?

Life in India changed me a great deal. Bear in mind that I came to India at the age of 24 and stayed fifty years. I had not actually intended to stay so long; Africa (Nigeria) was the original goal, and because of political unrest there I chose India rather by chance and spontaneously.

A fateful decision.

One could say so. In this time my longest stay in Europe was just over three months. India shaped me, it made me what I am, both in conformity with India and in opposition to India. In Germany I often heard I behaved like an Indian; in India I heard I had become a “Bengali.” A newspaper called me “an honorary Bengali.” Well, I consciously wanted to absorb the good sides of the Bengali temperament, but I also rejected some other aspects.

You speak of negative experiences.

Yes, for example it almost hurts me how middle-class people deal with the poor and less educated population. I radically reject class differences; likewise the way women are sometimes degraded. But I admire the great sense of family of Indians, their unwavering loyalty to the family, especially also to the elderly and infirm, and I often mention this in my lectures here, because this close family cohesion is lacking in Germany. Also the heart-warming vitality and cheerful nature of many young Indians do me real good. I write in detail about this topic in my book The Scent of the Divine. India in Everyday Life (Editor’s note: Patmos Verlag 2025).

You are involved in village projects.

Yes, more precisely in villages of Santals, indigenous peoples belonging to the “scheduled tribes.” I am committed to education, according to Tagore’s principle of holistic pedagogy.

Current Work & Future Perspectives

You now live again in Germany. Did you ever think of staying in India permanently?

Yes, very early I had applied for Indian citizenship, and it was also offered to me.

That in itself is quite an achievement…

But I did not take the step of giving up my German passport in order to obtain an Indian passport.

Why not?

I would have had to renounce all possessions in Germany, and thus also could not have inherited the parental home. I would have had to give up my German bank account. That seemed too insecure to me, especially as almost my entire income came from Germany and Austria – from publishers, magazines, radio stations, etc. – Since 2023 I have been living again in Germany, because I became seriously ill. A tumor was operated on. Since then I receive regular infusions, which tie me to Germany. I miss India every day.

A simple but very beautiful sentence. How do you shape your daily life today? Are there currently projects that particularly occupy you? You do not seem to me to be retired.

My work continues. I do write every day. After the operation I wrote and published The Scent of the Divine. India in Everyday Life. All over the German-speaking world I offer readings and discussions on this book, which, thematically structured, forms the sum of my fifty years of experience in everyday Indian life. I have also written another children’s book in English, my third (We Live Here, You Know. Niyogi Books, New Delhi 2025; in Bengali translation by Jaykrishna Kayal: Footpather Swapna, Ananda Publishers, Kolkata 2025), which gives me immense joy. Every single day I remember India. When I dream, I am always in India! My young friends, my peers, the temperament of the people, the atmosphere – I miss it all! In winter I will again go there for a month.

In your words one hears both passion and longing…

… and yet I try to connect to German and European reality. It is not easy. For I especially miss the easygoing, uncomplicated communicative ability of Indians. There: People talk to each other, visit each other, invite each other; here: exaggeratedly put, you only get to know your neighbor when he has died and you are invited to the funeral (both laugh).

Let us change the subject less elegantly: In recent years Germany’s interest in India has increased significantly – in business, politics, science, but also in pop culture. How do you assess this development? What are, in your view, the opportunities – and perhaps also risks?

India is gaining ever greater importance as Germany’s economic partner. Bollywood films are offered more and more frequently; the tourism industry is expanding with the marketing of “Incredible India.” Politics is becoming more prominent, but has generally been critically observed for a decade. But what about intellectual, literary, and generally cultural and scientific life in India – how much of that reaches us here in Germany?

Hardly anything?

Yes, very little. India is and remains an enigmatic country that very few really want to grasp deeply. Nevertheless: There are dozens of small and larger initiatives in Germany that support the underprivileged in India. Schools, agricultural projects, hospitals, slum and village development projects are emerging. More could be done if the government behaved more cooperatively.

You have always sought to bring India closer to the Germans. After decades of mediation: what is your personal conclusion?

For 30 years I wrote regularly for the feature section of the FAZ about Indian culture and society. I did radio broadcasts, gave lectures and readings from my books. I hope it had some effect. I do not know. The magazine Meine Welt and your internet portal have promoted a critical understanding of India. Did it have any effect? I do not know. Are we supported by anyone, from official quarters or from business? We continue, because our heart burns for dialogue with the best of India. Full stop!

I do not consider it measurable, but I believe it does have an effect, and much reader feedback confirms us. What future do you see for intercultural dialogue – especially between India and Germany?

We must take into view the entire spectrum of cultural life in India. Its rich literature, its differentiated social life, its village culture, the astonishing cultural life of the tribes and the mountain peoples. We should not cling only to clichés. India is more than elephants, snake charmers, and Mughal palaces.

Without doubt.

… and I promise a rich personal harvest if we engage with Indian philosophy, for example what I summarize in my autobiography under three keywords: “Unity in Diversity,” “Perspectivism,” and “Religion as Play.” Whoever engages with India in this way has the chance to change his life, his consciousness expands. He views his own life with new astonishment.

Words to the Next Generation

This brings me to the next generation – if you could give something to a young generation in Germany (and India) along the way – what would it be?

I would tell them: Do not believe that a tourist trip through India would open up the country to you. You can enjoy its vitality, you experience with shock the poverty and misery in the cities. But you remain voyeurs. Make friends among the young population, spend a few months as a worker in a village project, take seriously what you do. Get involved wherever you are. Be honest with yourself. Read a lot, also my books. Reflect on what this reading and your visits to India could, should do to your life.

Final word: Which values, insights, or perhaps also doubts would you like to share?

My doubts concern the belief of young people that the mobile phone and television would already show them the whole world. Far from it! Arrive in India and feel with all your senses and emotions how a new world unfolds before you.

We could not conclude better. Thank you for your time and all the best for the future.

Further book recommendations about Martin Kämpchen:

On the occasion of his 75th birthday, Martin Kämpchen tells in his autobiography My Life in India („Mein Leben in Indien“) of an extraordinary life in India, shaped by cultural dialogue, spirituality, and social commitment. As a renowned Tagore translator, scholar of religion, and long-time India correspondent, he offers a unique insight into Indian society from close proximity. Publisher link: https://shop.verlagsgruppe-patmos.de/mein-leben-in-indien-011368.html

India is moving ever more strongly into the global spotlight – but whoever really wants to understand the country needs more than headlines. After 50 years of lived everyday life in India, Martin Kämpchen conveys in vivid observations how the country thinks, feels, and lives – and thus opens the view to its cultural depth in his book The Scent of the Divine („Der Duft des Göttlichen“). Publisher link: https://shop.verlagsgruppe-patmos.de/der-duft-des-goettlichen-011574.html